Is a dust storm dangerous?

When a towering wall of dark clouds — thousands of feet high and miles wide — looms on the horizon, and moves quickly in your direction, it’s easy to imagine the worst.

Watching a dust storm blow in, you can almost imagine it will leave a broad swath of nothingness in its wake, like the devastation you’d see in a science fiction story. Fortunately, these storms are not like that at all — but that’s not to say they can’t be dangerous in some ways.

Dust storms, American-style

What surprises a lot of people is that huge, towering dust storms aren’t only found in the Middle East or Africa — but in the US, too.

The National Weather Service notes that dust storms and haboobs can occur anywhere in the United States, although they’re most common in the Southwest. They are, in fact, pretty much a yearly event in Arizona.

Dust storm or haboob?

What’s the difference between a dust storm, a sandstorm and a haboob — or are they the same thing?

A dust storm is formed when strong turbulent winds pick up loose particles of dirt and sand, creating a wall of wind that pushes across dry terrain. While they’re very similar, the particles caught up in the wind are smaller in a dust storm than in a sandstorm.

If there’s a wall of dust — like those seen above and below — that’s when a dust storm can be considered a haboob. (The word haboob is Arabic for “strong wind” — habb meaning “wind.”)

When a haboob-style dust storm is blowing in, from a distance, it looks like a solid wall of clouds close to the ground — very different to usual storm cloud formations.

Once you’re inside the wall of clouds, daylight instantly turns into a dusky evening light. All the dust that’s kicked up makes the air an orange-brown color, and the wind howls as it blows not just the sandy dust, but also leaves and litter and everything else that’s loose.

The wind also helps send a layer of find dirt into your eyes, into swimming pools, onto cars, and dusting everything else in its path.

Where do dust storms come from?

What causes these huge dust storms? In the US — particularly the dry, desert areas of the southwest (including California, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah and Texas — dust storms are most common in the summertime, often in the afternoon during monsoon season, when there is thunderstorm activity in the area.

Outside the United States, haboobs have been seen in the Sahara desert region, the Arabian Peninsula, Kuwait, Iraq, North Africa, Australia and Alberta, Canada.

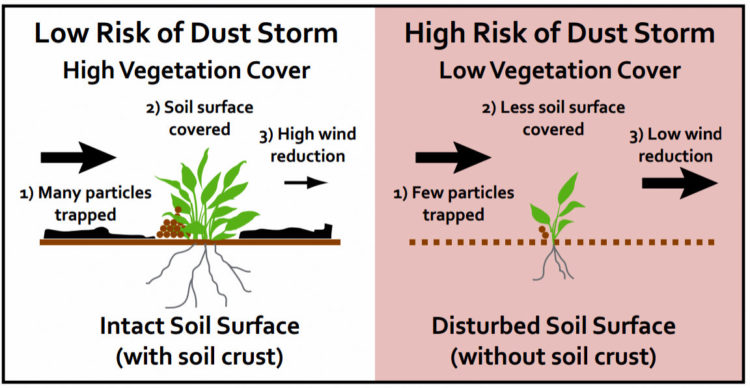

USGS information (and partner research) shows that two major contributing factors to the creation of these storms are low vegetation cover and disturbance to the surface of the soil.

It’s happening more often

“We’ve known for some time that the Southwest U.S. is becoming drier,” says Daniel Tong, a scientist at NOAA’s Air Resources Laboratory and George Mason University. “Dust storms in the region have more than doubled between the 1990s and the 2000s.

But it’s not just in the states. Research by the United Nations has also found that the frequency of dust storms is increasing in other parts of the world as well, including around the Sahara Desert.

According to the NOAA National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service (NESDIS):

It might seem small, but atmospheric dust is a big deal. Consisting (mostly) of tiny pieces of metal oxides, clays and carbonates, dust is the single largest component of the aerosols in Earth’s atmosphere, and it likely has a significant impact on the Earth’s climate, as it affects a wide range of phenomena, including from temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean to the rate of snowmelt in the southwestern U.S.

Dust may also affect hurricanes, as recent research based on data sets dating back to the 1950s suggests an inverse relationship between dust in the tropical North Atlantic and the number of Atlantic hurricanes during the past several decades.

That’s one big haboob

The photo below was taken as one of the largest recorded dust storms rolled into the Phoenix, Arizona metro area on July 5, 2011.

The National Weather Service termed it a “very large and historic dust storm,” and reported that, based on radar data, the storm is estimated to have reached a peak height of at least 5000 to 6000 feet, with the leading edge stretching for almost 100 miles — and the whole storm is said to have traveled at least 150 miles.

The NWS noted that there were several contributing factors to the storm’s intensity (all of which are common to dust storm activity — just not to the same degree as seen during this haboob).

Here are a few of the causes that worked in tandem to create this particular storm:

Monsoon: In Arizona, dust storms most often occur during Monsoon season — which usually begins each year around the middle of June, and lasts until about the second half of September.

Dry land: There was an ongoing drought in the area between Tucson and Phoenix, where rainfall since the end of the last summer has been less than 50% of normal.

Thunderstorms: In the afternoon, strong to severe thunderstorms developed east of Tucson. Thunderstorms in eastern and southern Arizona collided.

Gaining strength: The storms intensified as they progressed west, producing downburst winds in excess of 70 MPH, raising and collecting dust.

Force of gravity: Aided by gravity (as Tucson’s altitude is approximately 1500 feet higher than Phoenix) and additional downbursts from the parent storms, these strong outflow winds proceeded to race off to the northwest, with the leading edge moving at 30 to 40 MPH.

Are dust storms dangerous?

As freaky as the storms can look, haboobs and regular dust storms aren’t destructive like tornadoes and hurricanes. But as you’d imagine, driving is dangerous during the event, because they can massively reduce visibility, and often occur with little warning.

If you’re driving when a dust storm hits, the Arizona Department of Transportation says to pull off the road and turn your lights off. Put on your emergency brake, and be sure you don’t have your foot on the brake pedal.

Apparently, in reduced visibility, other people may see your car’s lights and attempt to follow — which is not a good move when you’re stopped. (For more specifics and tips, check az511.com.)

Don’t breathe it in

An issue that arises from dust storms and sand storms is the huge decrease in air quality due to the very small particles of dust, which are of concern because they can cause damage when they’re inhaled into the lungs. (Larger particles, on the other hand, get filtered out by your nose and throat.)

One other problem? Tong said that along with more storms, they see that Valley Fever is increasing in the same region.

Valley fever is an infectious disease caught by inhaling a certain soil-dwelling fungus — Coccidioides — that’s found mainly in the Southwest. It rides in and wreaks more havoc during dust storms, but is also found throughout the area. In 2017, the rate of illness was 98.8 per 100,000 people.

Says the CDC about the rather freaky illness:

Coccidioides spores circulate in the air after contaminated soil and dust are disturbed by humans, animals, or the weather. The spores are too small to see without a microscope.

When people breathe in the spores, they are at risk for developing Valley Fever. After the spores enter the lungs, the person’s body temperature allows the spores to change shape and grow into spherules.

When the spherules get large enough, they break open and releases smaller pieces (called endospores) which can then potentially spread within the lungs or to other organs and grow into new spherules.

As gross as that sounds, you can minimize the risk. In fact, the Arizona Department of Health Services says that the best way to avoid Valley Fever is pretty simple: avoid blowing dust, and stay inside during dust storms.

An estimated 40% of people who are infected will develop symptoms such as a cough, fever, fatigue, chest pain, night sweats, muscle aches and headaches. Some symptoms can last for weeks — or even months. Fortunately, most people with symptoms will get better without treatment.

So while a dust storm can look frightening — a huge wall of darkness rushing across the land, quickly enveloping entire cities — its greatest danger really comes from something so small that you can’t even see it.

An all-American dust storm: Amazing time-lapse of a Phoenix ‘haboob’

These time-lapse videos show a wall of dust moving through the city of Phoenix, Arizona,