How does the jet stream speed up plane travel?

You might hear pilots talking about headwinds and tailwinds, but how does the jet stream actually affect your flight? More to the point: What is the jet stream?

The jet set

You’ve seen that big band on the weather maps, and you know that it occasionally drags that cold, crisp air down from the north and makes you mutter under your breath about how the Canadians should keep their air.

But maybe you’ve noticed when you’re flying across the country — or the ocean — that your flight times out and back are different. So what’s the deal?

The air up there

While the existence of the jet stream — or at least the effects thereof — were first observed following the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883, it was Japan’s Wasaburo Ooishi who launched pilot balloons from a site near Mt Fuji and tracked their progress in the 1920s, establishing the nature of the powerful upper level current.

His work went largely unnoticed outside of Japan, however, and the German meteorologist Heinrich Seilkopf is credited with creating the term Strahlströmung — literally, “jet streaming” — in 1939, which we’re familiar with today.

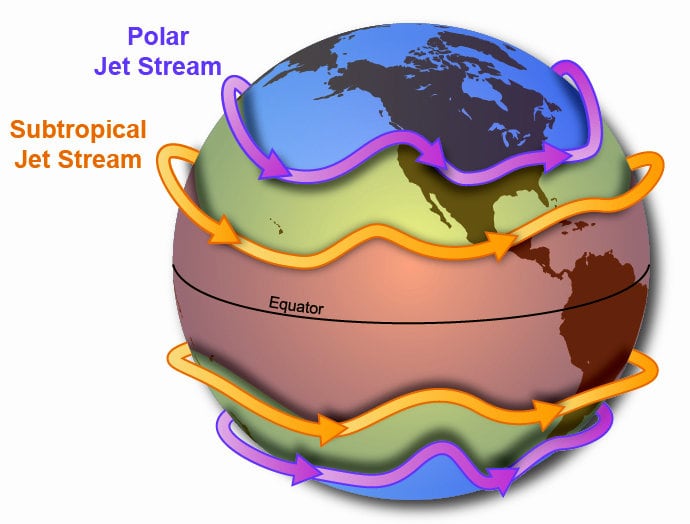

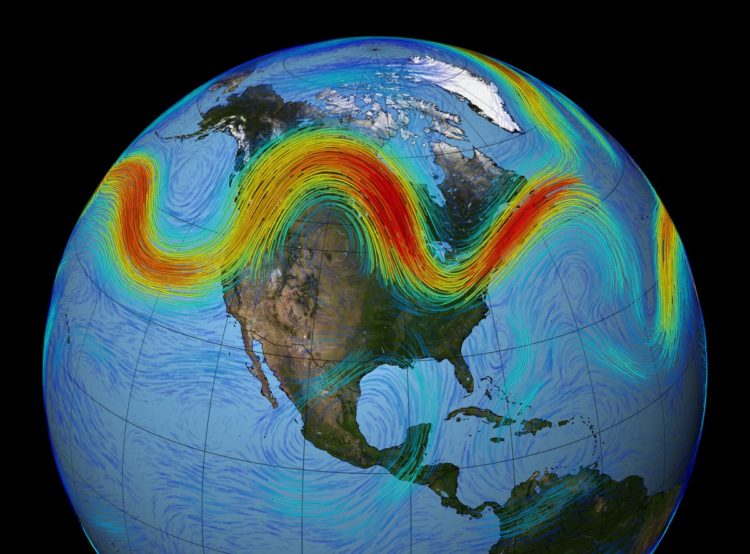

What it boils down to is, between altitudes of 23,000 and 39,000 feet, there is a fast-flowing, narrow air current that winds its way around the top (and bottom — the southern hemisphere has a jet stream, too) of the earth.

This band of air generally moves faster than 50 knots (or 57 mph), but speeds upwards of 230 mph have been measured.

Don’t spit into the wind

While the speed will fluctuate seasonally and based on other weather patterns, one thing doesn’t change: the jetstream always flows from west to east, due to the earth’s rotation.

MORE: What are the most dangerous airports for landings?

The end result, for you as an air traveler, is that when you board that plane in Los Angeles (in the west) bound for New York (in the east), it’s going to take you about 30 minutes less to get there than it will for you to return home — thanks to the jet stream.

If you fly even further, the effect is magnified dramatically. Pan Am discovered in November 1952 that if they used the jet stream while on a flight from Tokyo (west) to Honolulu (east), they could cut the trip down to 11.5 hours from 18 hours. For a propeller plane flight in the ’50s, that was a pretty major improvement.

This also results in fuel savings as well — estimates show that carriers can save hundreds of millions of dollars each year simply by planning their flights on wind-optimal routes.

So now you know one way that the weather can actually save you time!

What is the jet stream?

Check out this video from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to learn more.